Inside the fossil fuel divestment movement at Cal State

This article, written by CalMatters College Journalism Network Fellow Stephanie Zappelli, is available for republication. Zappelli is also a reporter at Mustang News, the student newspaper out of Cal Poly. Donate to CalMatters here.

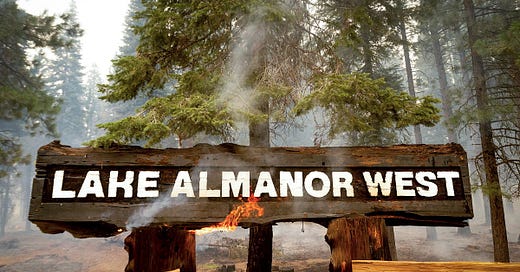

Ethan Quaranta seeks out nature when he needs to heal. He picked up that habit on annual family trips to Lake Almanor, where his great-grandmother grew up. There, on hikes, kayak rides, and in conversations about his family’s history, the 21-year-old California State University Monterey Bay student developed a passion for keeping spaces like the lake safe.

But this summer, the Dixie Fire tore through Lake Almanor, destroying his great-grandmother’s childhood schoolhouse and parts of the forest surrounding it. The loss strengthened Quaranta’s commitment to push the Cal State system to divest its money from fossil fuels, an industry that contributes to climate change and increases the risk of destructive disasters. He and other activists campaigned for the change for nine months through the student-run coalition Divest the CSU.

“I wasn’t just sitting around sulking in my feelings,” he said. “I was doing something to adjust what was causing them at the root.”

This month, Divest the CSU won a big victory when the university pledged to purge about $162 million in fossil fuel assets from its three major investment funds, citing both environmental and financial reasons. The CSU, the largest four-year public university system in the country, joins more than 60 United States colleges and universities that have committed to divest from fossil fuel companies, including the University of California in 2019 and Harvard University this year. In 2020, UC announced that its endowment, pension fund and working capital pools were fossil fuel free after selling more than $1 billion of investments.

The CSU’s Investment Advisory Committee voted 7-1 on Oct. 6 to divest. The fossil fuel industry currently comprises 3.2% of the CSU’s $5.2 billion of investments, said CSU spokesperson Michael Uhlenkamp.

Divestment was already on Cal State’s radar when student activists started their work, said Robert Eaton, an investment advisory committee member and the university’s assistant vice chancellor of financing, treasury and risk management. As climate change worsens, the committee anticipates more government regulation of fossil fuel companies, which could reduce their profits and the value of their stock, making them a risky investment, Eaton said.

He voted in favor of divestment and said he appreciated that students presented financial arguments alongside social and environmental concerns.

“It was productive, it was positive and it was an important part of the process that led to this decision,” he said.

Michael Lucki, another member of the Cal State investment advisory committee, cast the lone vote against divestment. In an interview, he said that the oil and gas funds had been some of the university’s best-performing investments this year.

“Just to divest it for global warming didn’t make sense from a fiduciary responsibility for financial returns,” he said. Fossil fuel companies are also the “most logical players” to develop renewable energy in the future, and should continue to be supported, Lucki added.

That’s an argument that detractors at other universities have also made, but Eaton countered that the system can always re-invest if fossil fuel companies pivot to producing renewable energy and prove that “they’re sincere about it.”

More than the money

Realistically, pulling $162 million over time is not going to financially affect a massive industry. But the purpose of divestment is not to make a financial impact on fossil fuel companies; it’s to make a political statement that fossil fuels are no longer safe to use, said Carlos Davidson, a San Francisco State professor emeritus who supported the effort.

“The political strategy of divestment is to call those companies out as bad actors,” Davidson said. “That weakens their political power.”

If the divestment movement makes society reject fossil fuels, politicians could have more difficulty accepting donations from those companies — which could make it easier for the government to regulate them, Davidson said.

The Cal State decision is important because every time a new university or investment fund pulls money from fossil fuels, the companies and the public get the message that fossil fuels are a more risky investment, said Tom Sanzillo, director of financial analysis at The Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis.

“In the long run the planet will largely be ok. It’s a matter of, will we be there, or not?”

ETHAN QUARANTA, STUDENT CLIMATE ACTIVIST

The impact of divesting on the international fossil fuel industry is a little more complicated, said Theodor Cojoianu, a finance lecturer at Queen’s University Belfast and a member of the Platform on Sustainable Finance at the European Commission.

In a January study Cojoianu co-authored, he and a team of researchers found that when there is a large divestment movement in a country, banks might start pulling money away from fossil fuel production in their own country, but potentially invest in fossil fuel companies in other nations.

“It’s hard to tell, for example, if the divestment movement … has really hurt the oil and gas sector,” Cojoianu said.

Limits to divestment

In 30 to 60 days, Cal State plans to sell their fossil fuel-related bonds and exit the Vanguard Energy Fund, which is a collection of fossil fuel stocks. This will remove $111 million of fossil fuel investments from their portfolio.

The remaining $51 million in fossil fuel investments resides in mutual funds, collections of stocks managed outside of the CSU. The university did not give itself a deadline to drop those investments, Eaton said. Mutual funds that don’t contain fossil fuels haven’t existed long enough to establish a record of success, so investing in them is riskier, he said. Replacing the university’s current mutual fund investments could take years, he said.

Students will need to keep the pressure on the university to divest as quickly as possible, said Kerrina Williams, the digital disruption organizer at Divest Ed, an organization that trains student climate activists in fighting for divestment.

Still, she called Cal State’s announcement “a big wake-up call for all the school systems.”

“If the CSU can do it, any school system can do it,” Williams said. “They organized like hell, and I think it just shows how possible this work is and how quickly it can happen.”

Another limitation of the announcement is that individual campuses, which have control over their own finances, will not be required to divest. Those campus endowments amount to about $1.3 billion, and because they are managed by campus auxiliary foundations, Cal State officials don’t know how much money they have invested in fossil fuels, Uhlenkamp said.

At least three Cal State campuses have already committed to divesting, including San Francisco State, Chico State and Humboldt State, according to Divest Ed.

The decision also does not impact CalPERS, California’s pension fund that includes university employees and retirees.

Students vs. fossil fuels

The move to divest at Cal State follows an onslaught of student activism.

In February, a handful of students started speaking at Board of Trustees meetings to advocate for divestment, and on May 2, the Cal State Student Association passed a resolution urging the CSU to pull its money from the industry.

A few weeks later, Cal State Chancellor Joseph Castro announced that the university would consider divesting from fossil fuels if it was a sound financial decision, spurring student activists to action.

By June, Divest the CSU had 50 active members and began meeting with university officials on Zoom, asking them to hold polluters accountable for their actions.

Ethan Quaranta, a student at Cal State Monterey Bay, helped lead a campaign urging the university to divest from fossil fuels. Joshua Label for CalMatters

Quaranta and his team reminded officials of a report from the International Energy Agency that said humans must make no investments in new fossil fuel supply projects starting in May 2021 in order to limit global warming to 1.5 degrees celsius and prevent serious climate disaster. Then he brought in his own experience.

He told the trustees about the Dixie Fire destroying parts of Lake Almanor, and reminded them that summer wildfires devoured the homes of students statewide. Divesting from fossil fuels was a way the university could fight climate change, which Quaranta told them was critical for the well-being of students.

When the university announced its decision to divest, Quaranta had a dance party in his room.

“I cannot dance, usually,” he joked. “It worked some type of miracle.”

Organizers with Divest CSU said they now plan to figure out which campuses are still investing in fossil fuels, and convince them not to — a potentially more difficult task because of the varying politics at campuses throughout the state.

“I think that climate change is largely a fight regarding humanity,” Quaranta said. “In the long run the planet will largely be ok; it’s a matter of, will we be there, or not?”

Zappelli is a fellow with the CalMatters College Journalism Network, a collaboration between CalMatters and student journalists from across California. This story and other higher education coverage are supported by the College Futures Foundation.