From incarceration to liberation: How Blake Krawl is making impactful changes to support formerly incarcerated students

Ana Acosta wrote this article for Long Beach State’s Daily Forty-Niner. It is available for republication or reference. If you think their work is important, you can support it here.

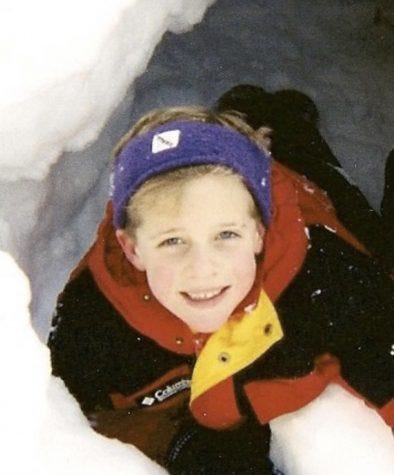

When Blake Krawl was 12 years old, he had his first drink of alcohol. At 16, he started experimenting with drugs. At 18, he became addicted to opioids and was living on the street and was in and out of jail.

Now, 28, he’s majoring in psychology at Long Beach State and plans to go to law school to become a public defender.

Krawl currently works as a lead student assistant for Project Rebound at CSULB. He is one of 51 students involved with the program dedicated to supporting formerly incarcerated students.

Krawl grew up in Idaho and remained there until he turned 18. When he was younger, Krawl felt alienated from his peers for having feminine attributes and his attraction to men. Despite having never experienced outward attacks for his sexuality, Krawl felt singled out by others.

“I couldn’t do anything about it,” Krawl said. “That’s what was shitty. You know, if it was something like a behavior that I could change I totally would do that to fit in with my peers. Not now, but back then.”

He hadn’t been out of the closet in high school, but people often singled him out, spread rumors about him, and uttered slurs. Those actions prompted him to drink and use drugs to relieve the anxiety that surrounded those emotions.

Krawl wanted others to focus on his “bad kid” behavior as opposed to wondering whether he was gay or not.

When Krawl was 15, his parents became aware of his drug use and sent him away to a rehabilitation program.

Krawl knew his parents had good intentions when placing him in the program, but after spending 15 months undergoing odd therapy tactics and soundproof rooms, he grew resentful when he returned home at 16.

“That’s when the hard drug use started,” Krawl said.

When Krawl returned home, he became addicted to opiates such as oxycodone and heroin. He graduated high school and moved to California in 2012 for college.

Krawl struggled to stay in school. He said there were times when he was able to maintain sobriety and get good grades, but then he would start slipping into his old habits of drug abuse, which would lead him to fail his classes and drop out.

Krawl had been in and out of nearly nine different academic institutions, and his parents eventually gave him an ultimatum. He could either allow them to financially support him through school and rehabilitation in an effort to maintain sobriety or he could go do drugs on the street.

Krawl chose the latter.

While living on the streets without any family to turn to, Krawl started up a history of repeated incarcerations. Most of his crimes included property theft, stealing, and drug possession.

Krawl’s first major arrest in California was for identity theft and for having possession of stolen property.

“Once I started getting arrested and got in the system, it seemed like it kind of just got worse,” Krawl said. “I continued to use drugs, and I don’t know, I guess my self-esteem definitely started dropping at that point.”

Krawl was aware that his habits of stealing and running in and out of people’s lives was unacceptable, but he was “so addicted to the drugs that [he] really wasn’t thinking about that or considering other people.”

Krawl said that the last time he went to jail it was because he cut off his GPS monitor.

He looked at his life and recognized that no one but himself was to blame for his situation.

“As crappy as it was to be there, this is like, this is all me,” Krawl said. “All the decisions that I’ve been making. You know, I can’t be mad at my PO [probation officer]. I can’t be mad at my family. I can really be mad at no one but myself.”

So Krawl called his probation officer, Tiffani Milstead, at 7 p.m. one December night, and asked to be picked up by the police so he could begin the steps to sobriety.

“Anytime someone has to go back into custody, that’s not a pleasant experience,” Milstead said. “Some of Blake’s struggles are because of things that happened while he was in custody. Knowing that he had to go back to that place was difficult.”

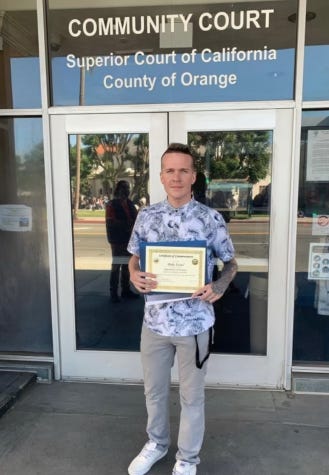

Krawl returned to drug court in Orange County, where he remained sober and returned to school.

While attending Santa Ana College to study psychology, Krawl became a founding member of the Project Rise student community, a similar organization to CSULB’s Project Rebound.

That’s where Krawl met professor Mark McCallick, who accepted the role as faculty adviser for Project Rise.

“Blake really created this movement to help other people, and it’s really caught fire,” McCallick said.

McCallick said his proudest memory of Krawl was when he gave his valedictorian address to the classes of 2020 and 2021 at the Santa Ana College graduation.

Krawl’s speech starts at 1:44:30

“When I found out he was going to be named valedictorian, I was almost as proud as if he was my son,” McCallick said. “Seeing him give his valedictorian speech, that was the highlight of my teaching years.”

Krawl graduated from Santa Ana in June 2021 and transferred to CSULB where he now majors in psychology with a minor in political science.

In December 2021, Krawl graduated from Opportunity Court, a voluntary program for non-violent drug offenders.

Milstead said she remembers when she would visit Krawl in his apartment and find him surrounded by flashcards. Krawl was studying for the LSAT.

Milstead said Krawl was in court one morning when he received his passing score and said members in court clapped and cheered for Krawl.

Krawl’s goal is to study criminal justice in law school to further support others who have stories just like him.

“I feel like there are so many things wrong with the criminal justice system,” Krawl said. “Some people may be like, ‘Oh, well, you’re just saying that because you were incarcerated.’ But it’s like something needs to change about it. Because the prison population continues to grow, and if nothing changes, nothing changes.”

Krawl said he was fortunate to have such a supportive probation officer and attorney, because that wasn’t always the case.

“Some of the stuff that I’ve been told by public defenders,” Krawl said. “Like, ‘you belong in jail’… it’s crazy. If this dude’s not willing to fight for me, then am I going to change?”

He hopes to be that support to other incarcerated individuals so they can make changes, make amends, and find opportunities in life.

“No one should ever be given up on, you know, no matter how many times they’ve been in prison, no matter how many times they’ve been to jail,” Krawl said. “They’re just people, people that are stuck in their own thing and stuck in a system that is really not trying to help them.”