A Social Worker Is De-Escalating ‘Life And Death’ Emergencies With San Luis Obispo Police

Chloe Lovejoy wrote this article for Cal Poly SLO’s Mustang News. It is available for republication or reference. If you think their work is important, you can support it here.

Content warning: This article mentions suicide and violence.

John Klevins answered a call from his wife, who asked why he was running late to get home.

A large ginger mustache and wide smile peaked through when Klevins adjusted his face mask as he chatted with his wife, to whom he promised he wouldn’t take more than another 15 minutes.

Above a pair of navy blue glasses, Klevins sported a baseball cap with a beaming sunflower emblem – the logo of San Luis Obispo’s Transitions Mental Health Association.

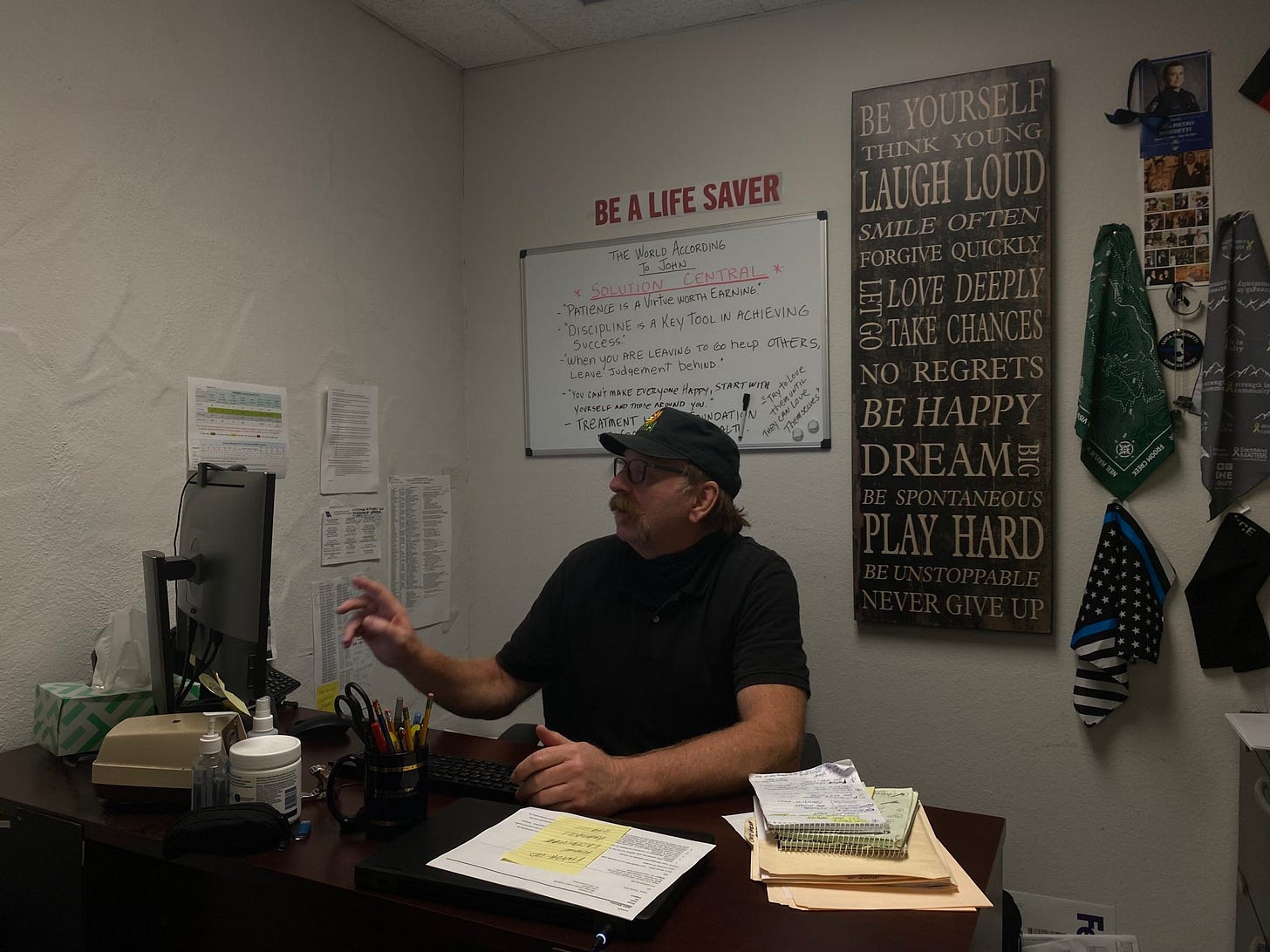

Klevins’ office is decorated with dozens of handwritten notes, scraps of paper, photos and dried flowers. He points to one card on the wall that reads “You are my happy place,” which was gifted to him by a woman he helped while she struggled with a methamphetamine addiction.

After jumping from her apartment window due to a hallucination she believed to be real, Klevins said he helped aid the woman’s injury and drove behind her ambulance on the way to the hospital.

Klevins joined the San Luis Obispo Police Department as the inaugural social worker on the Community Action Team (CAT) back in 2018, making literal headlines. CAT is responsible for responding to emergency scenarios that require de-escalation and mediation rather than police force.

Beyond emergencies, Klevins and his partner, Officer Tim Koznek, interact with San Luis Obispo’s unhoused community and refer individuals to housing and addiction-recovery agencies such as 40 Prado, CAPSLO, RISE and others.

Klevins is responsible for about 1,400 clients, a number far greater than the 100 clients per year initially required by the department. He and Koznek respond to crises including domestic violence, family intervention and suicidal ideation.

“I’ve come to realize that I have to compartmentalize my things, because I can’t count on my fingers and toes how many people have died that I’ve been involved with,” Klevins said. “I’ve watched people jump out windows and hit the ground right next to me, and so the level of severity of what I deal with is life and death.”

There are moments where his wife, Margaret Klevins, worries that when he doesn’t pick up the phone, it could be for the worst.

“There’s sometimes a little bit of fear, right? Because he sometimes walks in first and knocks at the door first,” Margaret said. “It’s his job to settle people down if they’re, you know, waving a machete or something.”

Over the phone, Margaret gushed about her husband and his career.

“We have a private joke with us that – I work for Bank of America – so I work for the evil corporation, but he saves our soul by working for the good of the world,” Margaret said.

After working in real estate for more than 20 years, Klevins found that making money wasn’t filling an emotional void in his life. He decided it was time to go back to school, and received his first masters in gerontology, the study of aging and the elderly. Klevins and his wife moved to Seattle, Washington where he ran a mobile non-profit for six years. After moving back to California, he got a second masters in social work at the age of 55.

“I got to a point where it’s like, you know what, I’d like to be involved in something where I’m helping people more directly,” Klevins said.

Only a month and a half away from receiving his full licensure as a Licensed Clinical Social Worker (LCSW), Klevins could move away from his position at the police department to a role that provides him a larger salary. A supervising position at the Atascadero Psychiatric Hospital is one such option, but that would keep Klevins from the line of fire.

“[The license] is not gonna do a damn thing in this job,” Klevins said. “I like this job. I like working for the police department. I like what I’m doing.”

Klevins doesn’t deny the danger that working for the police station poses to him. He pointed toward the bulletproof vest laying across the chair facing his desk. Out of his fairly unassuming work attire, the vest is one exception.

Klevins had several thoughts on the public’s perception of the police.

“I don’t think that I was ever a cop lover and wasn’t a cop hater,” Klevins said. “But now that I’ve had this, this experience for these number of years, I think we’re real fortunate to have cops willing to do what they’re willing to do.”

Klevins’ partner on CAT, Koznek, was present when the late Detective Luca Benedetti was killed in the line of duty in May of last year.

“If you’re sitting at home alone, and somebody is outside trying to break into your house, do you want to call a social worker?” Klevins said. “No, you don’t. This isn’t a trauma informed care moment.”

Checking the clock, Klevins realized he had already gone over the 15 minutes he promised to Margaret. But he’d be back in his office the next day, and the next, sticking with the police department and his 1,400 clients for the foreseeable future.